Break-downs; wall painting; energy vampires; killing his guitar; mission to Stansted. Complete with multi-media….

Back from 3 months in the USA with a poncho and a head full of crazy. After missing the previous flight home (“I’m not ready to come back, I haven’t finished here”), we’d managed to get him another ticket a week later. He begged the money to get a bus to the airport, leaving his home under the bridge with a tramp in Baton Rouge near New Orleans. We knew he’d got to the airport as he’d talked a businessman in the lounge into letting him send an email from his laptop. Tenterhooks, a late night, an early morning, flight times off the internet…

Ross walks out of arrivals at Heathrow terminal 3 on Friday 16th November at 7am. Back from destitution in New York. Back from living as a troll under a bridge near New Orleans. Back from the worst of our night terrors riding a wave of relief.

At least he’s not dead.

He’s hairy and smelly.

Unsurprisingly, his looks and behaviour are feral, he constantly glances round as though expecting a band of white coats to materialise and take him away. He smiles when he sees us, but is still wary as we converge into a huddle of arms, jumpers, beards and emotions.

“Hi Ross.” He pulls back and stares intently into my eyes. “Dad, if you try to have me sectioned, you’ll never see me again”. His first words. First impressions are so important. For a moment, I’m totally thrown by the contrast between the feelings coursing through me and the blunt reality of his words. I believe him. Then he’s my son again and long-held tension relaxes into relief and exhaustion.

We drive home (only 20 minutes) chatting inconsequentially, an unspoken compact keeping things light and superficial. He’s safe in the back of the car, an experience overlaid with past memories of family outings. I keep looking at him him in the rear view mirror whilst pretending to stretch.

For a few days, there’s a honeymoon period – he sleeps a lot, like a hippy hedgehog hibernating under the duvet. We know that psychosis has been spreading through his mind like metastatic cells, but, for the moment, we just want to feel him here, to hear him, smell him. Simple, physical, experiences. We try to ignore everything else, a willing suspension of knowledge for a moment of relief. Soaking-in our son and watching him and Owen brothering each other like guitar wielding puppies.

Ross needed familiarity (in the true sense of family-arity) and reassurance that he wouldn’t be sectioned or arrested. As the familiar became familiar again, he began to relax, to take the changes in his life for granted – and to swing increasingly wildly between brief moments of lucidity and fully blown delusions. Much later, we sat in the garden one Friday afternoon shortly before Ross was sectioned. The sun was shining and I’d gone home early, utterly exhausted. Ross showed up (hadn’t seen him for a while), and we just sat and chatted, father and son. Told him I loved him, hugged him. An hour of simple connection (ignoring some of the slightly weird conversational gambits), talking about holidays and music, avoiding “everything”. I needed that. The sun was warm and my son was warm. An hour later, he was mad again, screaming at me in the kitchen.

It is difficult to describe just how stressful the oscillations between filial affection and “autistic” manipulation and delusion would become as my emotions were repeatedly, and sometimes violently, flipped between extremes. I felt like the copper conductor in a cable when you can’t find the pliers, being bent back and forth and back and forth: hope – despair, hope – despair, love – anger, love – anger. In the end, you run out of ductility, turn brittle and the cracks start to appear.

My own mental state deteriorated over the next several months, swinging between obsession and depression, between numbing apathy and exhaustion with the occasional freaked frenzy. Looking back, I’m both ashamed and quite proud of some aspects of my behaviour as I lived on the dividing line between functional and collapsed. I’d meet other carers (a term much used by the mental health services, but which I really, really dislike) who hadn’t made it (breakdowns, early retirement etc) and some who still managed to function under circumstances that left me humbled by their resilience. I slipped over the line several times as Ross had a major breakdown (emergency call-out of the crash team), killed his guitar, got picked-up at Stansted trying to leave the country, painted his room madness, threatened his mother and assaulted me….

Nothing, however, was as bad as the increasing sense of loss I felt as I watched Ross gradually losing himself, piece by piece. It was like watching an eagle, planing high with the world beneath his wings turning into a battery chicken, dreaming mad eagle dreams and convincing himself that scratching about in a square foot of earth was a meaningful life. Little by little, it felt as though his soul was eroding away.

Ross’ case worker was brilliant. She saw him quite regularly, even hunting him down when he went elsewhere. Despite his mental state, Ross seemed to build-up a begrudging respect for her as she was experienced enough not to take any shit and to be honest with him. We had a very strong sense that she was on our side, doing her best to build a case for sectioning.

Sadly however, the rest of the mental health services appeared unable or unwilling to act. It seems that under the Mental Health Act, everyone had to stand-by and watch as Ross self-destructed. “Everyone” being the early intervention and crash teams, doctors, psychiatrists, case worker, us, friends et al. They all knew, admitted and discussed the fact that he was seriously psychotic and that his chances of a full recovery were deteriorating every day that went by without treatment. But “…there’s nothing we can do. He’s too articulate, and wouldn’t necessarily break-down during a sectioning interview. Not only that, but if we did succeed, he’d be out on appeal within a couple of weeks. We just have to wait (if only he was thick)….” Whilst this was utterly obscene and morally repugnant, apparently, it was impossible to do anything about it.

So I started to record things. I had this mad idea that, if I could put together enough incontrovertible and independent evidence of his mental state, somehow it might be taken into account, be taken seriously and some action would be triggered. Utterly naïve: Peter against the system. But I had to try something, anything. I couldn’t just stand by and watch it happen, watch Ross losing more of himself every day. Despite having built up a case that would have stood up in a court of law, it seems that evidence counts for nothing when it comes to interpreting the Act.

Losing Faith

When my grandmother died in hospital when I was 19, it was an obscenity. They had forcibly kept her alive for weeks and weeks after she had given up and decided that she didn’t want to go on. From my granny to a husk in a score of days. I hated visiting her. I didn’t want to see her like that, to be forced remember her as what she had become. And I hated myself for feeling that way. I wanted to remember her as she had been, not the way she had become. Faced with the day-to-day reality of coping with him, I began to find it more and more difficult to remember him and to keep faith with the essential Ross. Unless drugged, I’d wake in the low hours of the night, the hours when everything is hopeless and there are still 173 long minutes to endure before the alarm goes off. The hours when the mind-loops come for you.

Sometimes, with images of the previous day projected on the screen of night and with worries about where he was and if he was OK endlessly in my head, I’d try to play “Don’t Fade” (his song for me) in my mind or to imagine Ross and Owen playing guitar or burrowing on the beach together. Wanting and needing to hold him whole in my head, to remember him, to beat down the fear that he’ll never be able to come back. Tears I’m too tired to wipe. It’s 03:53am.

Months later, after Ross had come out of hospital, I wrote about these feelings in a poem, Dis-Chord, hoping that he would turn them into a song. This was a blatant attempt at occupational therapy on the family holiday a few days after he came home. We sat in the shade under a tree in France with his guitar and turned the words into the (somewhat different) lyrics of “Song of Sickness” whilst Ross wrote the music.

Dis-Chord

All the music that’s in you

It sang through my mind every day

Both our feelings entwined with the rhythms

That won’t go away

Then the harmony you’d found

Was turned to dischord in your head

Your beautiful sound it was muted

And then it was dead

I feared I’d forget you

As echoes of you fade away

A cacophony of voices destroying

The beat of your day

Your music had gone from you

You de-composing your head

As you scream in my face I remember

Your lyrics instead

Awake in the night, I am

Listening for something that’s gone

I strain with my ears for the ghost of

A hint of your song

I cling to the memory

Of your rhythm that beats in my heart

Your violent assault just reminds me

How gentle you are

Peter Wilson August 2008. For my son, Ross, suffering from psychosis. He is a very talented musician, but at one point, he killed his guitar…

Song of Sickness.

Recorded live on World Mental Health Day, October 2008 – his first time on stage post hospitalisation.

The Breakdown

I’d persuaded Ross to come down the gym with me, in the naïve hope that the exercise would improve his mood. He was very chatty in the car – it just felt so normal, a little male bonding. At the gym, he spent some time on the rolling road, but then got distracted and disappeared, later to be discovered staring in fascination at pictures on the walls.

Ross commentary 2010

There was always some strange logic to my behaviour, mostly it consisted of linking together various disparate ideas and memories and believing that they meant something highly significant. For example, when I was down the gym getting lost among the pictures that hung on the corridor walls, I believed that I was attracting my ex-band members back into my life because (now bear with me on this one…) I’d painted some pictures of them during an A-level art project and I’d linked the predominant colours of the pictures to represent their spirits. Therefore, when I was looking at certain colours in other pictures, I believed I was communicating with their spirits and drawing them (through the hidden mystical connections in the universe) back into my life. Interesting…

More father-son repartee on the way back home in the car. Pulled up on the drive and then….

…sudden screams, “…someone is telling me I’m not well”, tears, shouting, head on my lap in the car, “…dad, dad, dad, help me, I’m evil… I’m not well”

Ross “pretends” to have a break-down

I get him indoors and it’s as though a switch has been thrown when Owen comes down the stairs. “What’s up?” “Nothing dude”. But then he breaks down again in the lounge, sobbing, screaming – “not well, evil….”, lying on the couch with Gillian, Owen and myself hugging him, holding him, trying to reassure him, to comfort him. We call the emergency number for the Early Intervention crash team.

It’s deeply disturbing to experience so much anguish in your son, in your brother. Such fear and pain. The sounds, sobbing, screaming. The words “…someone keeps saying I’m not well, I’m evil, evil…”. It goes on and on and you just hold him. You say such simple, trite things, but with such feeling, as though you could create aural amulets that will ward-off the delusions and ease the suffering. After an age (but which was probably only 15 minutes in the real world outside our heads), Ross gradually subsides. We sit and hug and get him a drink, as though he is once more a five year old waking from night terrors.

The “breakdown” – Ross writing post hospital

I did it on purpose. That’s what I said anyway, whether or not it was true of course was another story. But, no I genuinely do believe that I had a reason at the time to go so extreme. The whole idea was that I was trying to show my Dad the impact he was having on me by continuing to call me “unwell”. I basically acted out breaking down to try to show him what a negative effect he was having on me. Because I was not happy with being called “unwell”, it had so much stigma attached to it, it made me feel like I was going crazy, not that I was going through something that happens to many people of all ages. So I started shouting and screaming things like “someone keeps saying I’m evil, someone keeps saying I’m NOT WELL, I’m evil, I’m evil, who keeps saying I’m not well, who is it?”.

I did this in the full knowledge that at any point I could stop and just say, “look what you’re saying is really beginning to annoy me” – but whether in reality I actually could is another matter entirely. I remember alternating between screaming and shouting to being very calm when Owen came down the stairs, which kind of showed to me that I did still have some element of control. So, well, who knows! It all gets a little bit weird when you go through mental illness.

The crash team arrives only half-an-hour after our call. Eventually, we will have cause to get to know the whole team, but this is the first time and we have no idea what to expect. The two of them come in, bringing with them a reassuringly bracing blast of reality and professional pragmatism. They get the history and talk to Ross, asking him about the experience, how he feels, whether he understands what is happening. They don’t pull any punches, but calmly and matter-of-factly discuss his symptoms and the options. They get him to agree to take something to calm him down plus an anti-psychotic to help him regain some control of his feelings and mind, to damp-down the random thoughts and impulses. He agrees, and one of them disappears into the night to raid a local pharmacy. Ross takes the tablets and we talk with the team. It is massively reassuring to discuss what has happened with them. Whilst it is new and frightening for us, it is part of their regular experience, one that is familiar and which can be turned from a helplessly emotive event into something that can gradually be evaluated more objectively.

They arrange a regular schedule of visits (starting the next day) to talk to Ross about the help and treatment options at home as he is disinclined to go to the New Horizons (mental health) centre. Our expressions of gratitude as they leave are heartfelt. Peace descends. A bath and then onto our bed for more hugs and quiet talking. Owen goes to his room whilst Ross lies across our bed in his fluffy dressing gown, sleepy and cuddly. There’s a feeling of closeness and a hope that, finally, we may have made some kind of breakthrough.

No chance.

And it’s all the more stressful and painful to feel some hope, and then to have it thoroughly shredded.

Drug Phobia

They came in pairs, at arranged times. I’d come home from work to attend the meetings and Ross would sometimes be up – whatever the time of day. They are called the Early Intervention Team, no matter what time they arrive.

The day after that first breakdown, there was a long family discussion with the team and Ross, with him being only intermittently communicative. They discussed his situation, behaviour and feelings, being quite blunt about what was likely to happen if he didn’t get treatment. That ultimately he would end up being sectioned against his will and that he would be treated anyway, with no control over what happened to him – and that the longer this went on, the lower the chances of a full recovery. So, a choice: voluntarily start the process of treatment and have some control over what happens, or end up with no choices and no control and much less likelihood of making a full recovery.

Despite his insistence that the problem lay with the behaviour and thoughts of everyone else, in the end he promised to engage in the process and to take medication. He was, of course, lying. That evening he said he would take his medication and supposedly took one pill, but then refused anything else. After all, why should he take powerful drugs when he was developing a higher consciousness and all the mental issues were ours and others. Given that’s how he felt, he had a good point. However, his reaction to the suggestion of taking medication, as he had promised he would, was extreme, almost phobic.

Drug Phobia

He pretended to take tablets when supervised and hid them when unsupervised. Other than during the team home visits, he refused to engage at all. Being psychotic doesn’t mean you’re stupid or lack cunning.

Ah there were moments when I thought I was controlling the universe too… Once I was playing with the dinner table arrangements… I was trying to get my Dad to stop drinking red wine. At the time I thought it symbolised blood and that it was feeding their energy vampirism. I firmly believed that they were energy vampires and that they were literally sucking the energy out of me and making me depressed. Boy did I believe some weird things at that time…

The Phoenix

I remember this painting that I downloaded from the internet that was of a Phoenix. The giant bird was just flying free of a mud/tar pit full of brown sludgy monsters. To me, the bird symbolised myself and the monsters were my parents and the mental health team which were all the people who were trying to pull me down into the black sludge of doom. That’s genuinely how I felt at the time too. I really felt that everyone had turned against me and that they were all trying to stop me from becoming the highest person I could be.

I also remember making some crazy little cartoons that technically were quite amazing, I remember being very proud and very fascinated by the drawings I was making and I was totally absorbed in every tiny little detail. I made a cartoon for a device that I thought would revolutionise family communications. Basically, I called it the Phoenix (at the time I was obsessed with the Phoenix), it symbolised my dissolution of my old identity and my rebirth as a spiritual being, a butterfly that had transformed by the light of consciousness.

If you don’t understand what I’m going on about, it’s okay, I think I’m the only one that did, and I’m not too sure if even I do now…).

So, I called this device the Phoenix and the idea was that basically it was a Dictaphone that I sellotaped to my door and would record messages on to communicate with my family. I thought this would revolutionise family communication because you could leave voice messages for people which would include the added value of being able to hear the tone of voice of the person recording it, thus giving it an emotional edge over just a plainly written note. God knows how or why I came up with that! I was full of ingenious but pretty useless ideas like this during that time. I spent pretty much all of my time coming up with new ideas for things I could do and then writing them down in one of my many little books. Oh, everything made sense to me at that time.

Everything I did was full of purpose and meaning and I absolutely knew what I was doing all the time. Do you see what I mean about the fun aspect of it? It was a highly creative time for me, although I did not actually produce very much in the way of works, (a lot of journal entries, some cartoons, some small pictures) I was constantly coming up with new ideas about cool things to do. I was loving every minute of it.

My dad was particularly upset with my obsession with the Phoenix. He thought that I thought that I was the Phoenix, that I had created an alter ego for myself. He listed such qualities as “distant,” “no empathy”, “no compassion” “isolated” as compared to my other ego “Ross” which he described as “helpful”, “compassionate”, “creative,” “empathetic” and so on. Little did he know that it was not an alter ego I had created for myself, but a power I thought actually existed within myself! I even began calling my powers of healing “phoenix powers” as can be seen from some of my cartoonised journal entries.

A Complete (and Desperate) Idiot Attempting to Appeal to Rationality

At one point, because Ross was making so much effort to rationalise his behaviour and beliefs, and was constantly writing everything down, I thought I’d try to plug-in to his obsessions with a written diatribe of my own that I gave him. I’d try anything, including clutching at really stupid straws which I’d then try to thrust into his hands.

Looking back, whilst I know I thought I was trying to understand, it was probably much more for my benefit than for his. It was a stress induced displacement activity and an attempt to make sense of the circumstances in my own head. I didn’t know what I was doing and behaved like a combination of dad and utter dick (this with the more relaxed wisdom of hindsight and much new understanding). Don’t do this if you ever find yourself in my position, just don’t…

Philosophy in the kitchen

Ross felt that our worries about him were sending waves through the ceiling – or across the Atlantic – that made him feel ill, that were sucking the life out of him…

Burns night meal with friends, 2019. Ross burns bright, the life and soul. 6 weeks later, we use the anniversary of my dad’s death as an excuse to visit the crematorium together, followed by pub lunch. He is – on edge. After food he becomes vocally aggressive, shouting. I have to leave. That evening he emails. He simultaneously never had a mental health problem (my having him sectioned was abuse) and all his mental health problems were caused by me. Schrödinger’s psychosis.

Burns night meal with friends, 2019. Ross burns bright, the life and soul. 6 weeks later, we use the anniversary of my dad’s death as an excuse to visit the crematorium together, followed by pub lunch. He is – on edge. After food he becomes vocally aggressive, shouting. I have to leave. That evening he emails. He simultaneously never had a mental health problem (my having him sectioned was abuse) and all his mental health problems were caused by me. Schrödinger’s psychosis. I spend 2 months putting intense pressure on the local mental health services and finally succeed in persuading them to act. They call to say they will turn up with the team to assess him – on the morning after he burnt down the shed (in which he had been semi-living) in the night and disappeared to, as we later discovered, Bournemouth. I contact the Bournemouth mental health services (local services doing chocolate teapot impressions) and, eventually, he is picked up by the police and taken to Prospect Park hospital in Reading for assessment. Relief is too mild a word. BUT. Fleeting. I’m told that he’s a “trustee”, allowed to come and go as he has promised to be treated in the community. I’m told he will shortly be released into that imaginary community…

I spend 2 months putting intense pressure on the local mental health services and finally succeed in persuading them to act. They call to say they will turn up with the team to assess him – on the morning after he burnt down the shed (in which he had been semi-living) in the night and disappeared to, as we later discovered, Bournemouth. I contact the Bournemouth mental health services (local services doing chocolate teapot impressions) and, eventually, he is picked up by the police and taken to Prospect Park hospital in Reading for assessment. Relief is too mild a word. BUT. Fleeting. I’m told that he’s a “trustee”, allowed to come and go as he has promised to be treated in the community. I’m told he will shortly be released into that imaginary community…

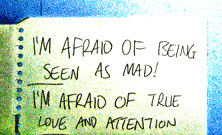

Killed his guitar in the woods on new years night, videoed himself painting his room red and dark green, and put up signs like these everywhere.

Killed his guitar in the woods on new years night, videoed himself painting his room red and dark green, and put up signs like these everywhere. “Yet to be named” was the last thing Ross achieved before crashing. Re-released as with new band as “Consumed in self”.

“Yet to be named” was the last thing Ross achieved before crashing. Re-released as with new band as “Consumed in self”. Smoked dope for a while, but then tried to give up following some scary symptoms. Wrote “Blame Marijuana”, prescient, but sadly too late…

Smoked dope for a while, but then tried to give up following some scary symptoms. Wrote “Blame Marijuana”, prescient, but sadly too late… While I was comatosed

While I was comatosed Get him a doctor

Get him a doctor Let me be nothing

Let me be nothing Going Home

Going Home Song of Sickness

Song of Sickness Chaos

Chaos Hugging Barbed Wire

Hugging Barbed Wire  then where will you go..

then where will you go.. Melancholy

Melancholy  Don’t Fade

Don’t Fade